The list of the composer's works that have been performed at the Salzburg Festival over the decades is impressive. From Artikulation in 1958 to the world premiere of the revised version of the opera Le Grand Macabre with Esa-Pekka Salonen and Peter Sellars in 1997 to orchestral and chamber concerts in recent years, the composer's music has always been present in Salzburg - and with it the great performers of his music. These undoubtedly include violist Tabea Zimmermann and pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard, to whom György Ligeti has entrusted world premieres of his works.

We publish the interview with the kind permission of the Salzburg Festival.

Ms. Zimmermann, Mr. Aimard, you have both performed regularly for decades at the Salzburg Festival. What do you associate with Salzburg?

Tabea Zimmermann: Ever since my short, but intense studies with Sandor Végh in 1985/86, Salzburg has been special to me.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard: First of all, I think of the city itself, of unforgettable performances and specific concert programmes at the Salzburg Festival going back decades, formerly conceived by Hans Landesmann and Gerard Mortier, today by Markus Hinterhäuser and Florian Wiegand.

Can you both remember your first encounter with Ligeti’s music?

Tabea Zimmermann: I was first introduced to Ligeti‘s music and his study of patterns and forms by my late husband, David Shallon. To this day, I find the subject of man and machine fascinating. One example is the influence of Nancarrow’s player piano rolls on Ligeti’s Études.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard: The first time I heard his music, I was eight or nine, and it was at a concert in Lyon. As a performer, I only encountered him later, as a member of the Ensemble intercontemporain, when I played his Chamber Concerto, which never ceases to fascinate me.

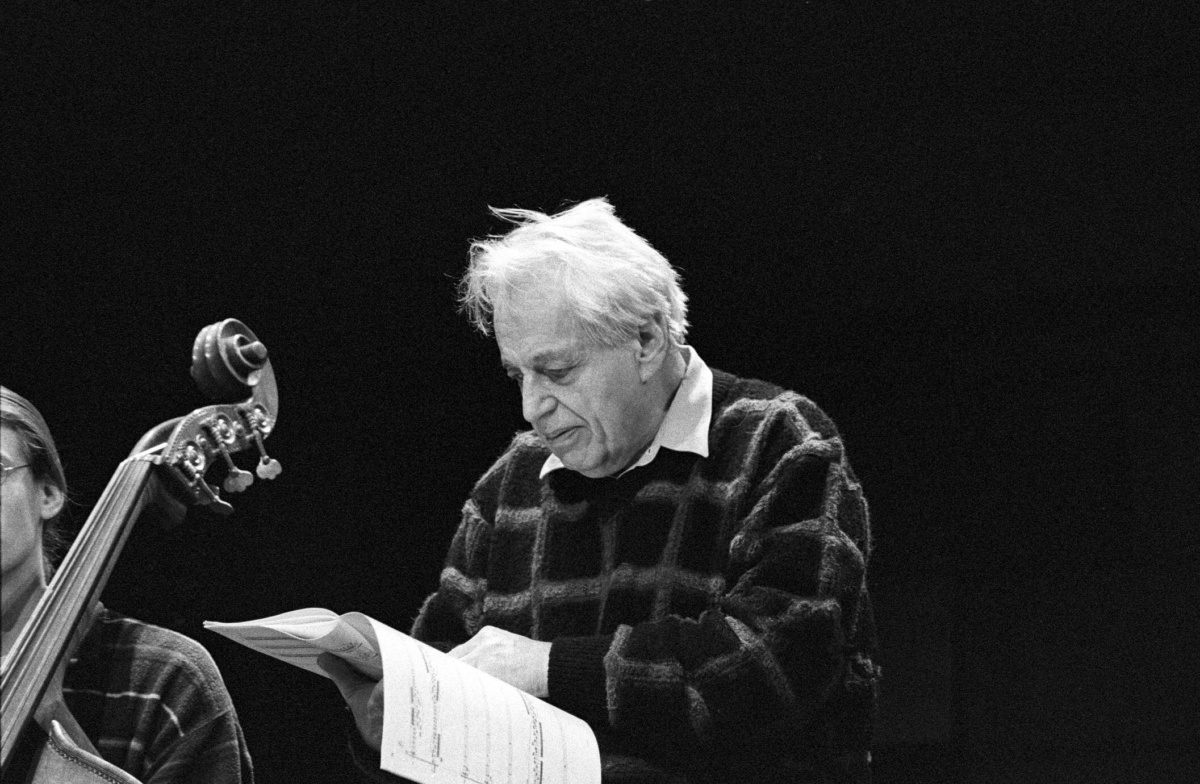

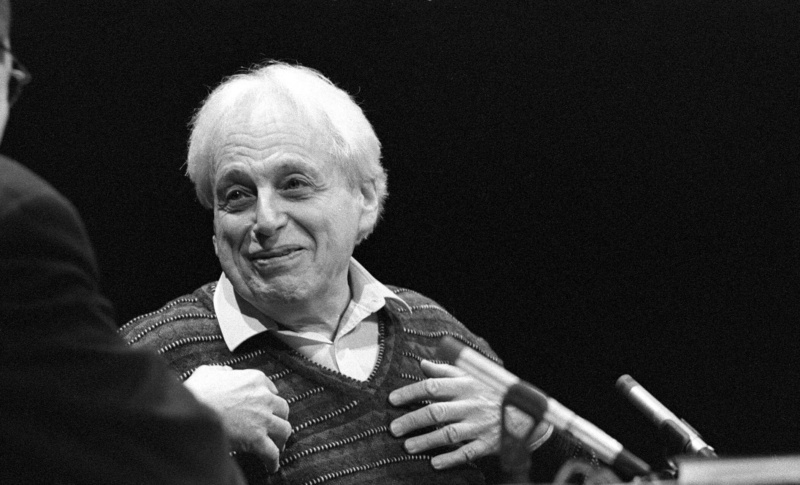

You both also knew György Ligeti well on a personal level. How would you describe him, as a man and as an artist?

Tabea Zimmermann: What I found striking was the fire that burned within him. He seemed like a restless seeker to me, never sparing himself or the people around him.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard: To my mind, he embodied great independence and inventiveness. His broad education was as original as he was as a human being. He had the courage to follow his convictions. His demands were notoriously feared, but they concerned mainly himself and his craft, which he put to use serving his overflowing imagination. His life was marked by personal tragedies, which he faced with a strong sense of humour and absurdity.

You both gave world premiere performances of works Ligeti dedicated to you, rehearsing them with him. Do other musicians ask you for advice when it comes to interpreting his pieces?

Tabea Zimmermann: Mostly, his notation is so clear that direct questions regarding the understanding of his works are rare. That is a great quality of his manner of writing. I can imagine that it is very hard for a composer to let go of their own work and entrust it to performers. In this sense, it is sometimes difficult for a performer to confront the composer, feeling their demands or clear ideas, but experiencing one’s own inabilities as a limiting factor. For me as an artist, it is probably those processes which led to the most intense growth.

You both teach at renowned music academies. Do you feel strongly about introducing students to Ligeti’s music and passing on your first-hand experience?

Tabea Zimmermann: Of course I pass my experience on to young people as best I can. However, this is less with regard to a performance tradition and more about encouraging them to expose themselves as fearlessly as possible to different schools, sounds and notions, and to experiment. I learn as much from the young people as they do from me. I find it fascinating how a collective sense of music and culture can grow, how thoughts can evolve across generations, undergoing further development independently of time and place. For example, after completing the third movement of the Solo Sonata, Ligeti said: “I have an idea for a scherzo, but I can’t write it, because Hindemith already composed it!” He was referring to the fourth movement of Hindemith’s Solo Sonata Op. 25/1.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard: When you have received a creator’s advice on performing their pieces, of course you have the responsibility of passing the information you have received on to the next generation. I am pleased when students play Ligeti’s works not only with the necessary technical ability, but also with the corresponding stylistic knowledge. In order to aid the dissemination of this knowledge, I participated in the development of an online platform dedicated to Ligeti’s music.

In general, you both came to contemporary music early in life. How did this interest develop?

Tabea Zimmermann: One reason was sheer necessity (laughs). As a violist, I had to struggle early on with the fact that there is relatively little first-rate original literature for my instrument. I recognized quickly that it was also an opportunity not to have to be measured against and struggle with the canon of great violin concerti, but instead to learn new works, being much closer to the process of composing and learning from that. I am fascinated by the view, or rather its acoustic equivalent, of the process, to shape and develop sound in the moment, playing as a creative force. This attitude completely changed my interpretation, also of older repertoire works. It gives me great joy when I can let my listeners participate, when we experience the thoughts and sounds of composers together as if for the first time. This requires a playful openness, also from the listeners, a fearless will to discover, instead of an urge to judge.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard: My very first professor of music introduced me to a broad musical spectrum, and of course this included a lot of New Music. Exposure to composers with a unique world-view challenges our own creativity.

One additional question for Ms. Zimmermann: at this year’s Festival, you are playing Ligeti’s Sonata for Solo Viola. The outside movements are dedicated to you, and you gave the first complete performance of the work in 1994. Has your perspective on it changed since then, and if so, how?

I went through several phases of my artistic development together with the Solo Sonata, and I’m sure these are reflected in the interpretation. Before the world premiere, the technical difficulty of these six movements, each challenging in a very different way, was the focus. After a while, I suffered various phases of fear, wanted to please Ligeti, but had not arrived at the point where I could confidently assume that I could do what he demanded and wanted from me. I also let the Solo Sonata mature during various periods, entrusting it to my subconscious, working on many individual problems with students, and was therefore better able to observe the music from the outside, somewhat detached from my own difficulties. This helped me enormously in finding a new approach and returning to the Sonata’s issues with new relish.